By Lauren Ciriac Wenger

Since the 15th century, individuals have created needlepoint samplers to demonstrate or practice their embroidery skills. Produced throughout Europe, the craft traveled to the New World with colonists. The Hershey Story’s artifact collection includes several samplers from the 18th and 19th centuries that demonstrate the craftsmanship of Pennsylvania Germans.

Until the rise in popularity of commercially manufactured clothing, sewing was an essential and practical skill. Not only did women need to know how to sew clothing and linens, but they also marked sheets, pillowcases, and tablecloths with their initials. Girls practiced stitches, patterns, and lettering by making samplers from linen cloth and various colors of silk, wool, or cotton thread. Customary Pennsylvania German sampler motifs included flowers, topiaries, deer, birds, hearts, houses, and stars. Since it was important that girls learned and memorized religious and moral verses, these were common additions to samplers as well.

Pennsylvania German girls spent their adolescence perfecting their sewing skills for future roles as wife and mother. They were taught either at home from older, more experienced relatives, or at school. When the designs on samplers are very similar, it is likely they were made by girls who had the same instructor. Yet a sampler can also contain elements that were very personal to the maker. Embroidered houses sometimes looked similar to the maker’s own home or the maker would incorporate important initials into the design, such as those of her parents or siblings.

Nine year old Susan Gish of Hummelstown, Pennsylvania worked the above sampler in 1834. There are floral and diamond patterns, along with vowels stitched in all capitals.

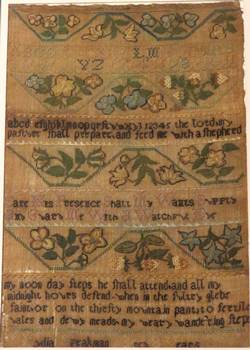

The oldest sampler in The Hershey Story’s collection was made by Lydia Speakman in 1784. It most likely originates from the Philadelphia area, but possibly Susquehanna or Chester County. It features a flower and leaf motif throughout, the alphabet at the top, and part of a poem written in 1712 by Joseph Addison, which says:

“The Lord, my pasture shall prepare, and feed me with a shepherd[‘s]

Care His Presence Shall My Wants Supply

And Guard Me With A Watchful Eye

My noon day steps he shall attend and all my midnight hours defend,

when in the sultry glebe faint, or on the thirsty mountain pant,

to fertile vales and dewy meads, my weary wandering steps”

During the 150 years prior to being added to the museum’s collection, exposure to light and humidity caused the fabric to yellow and threads to fade. Some of the discoloration is also the result of unavoidable aging.

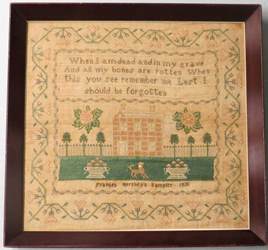

Frances Hershey (later McDade) created this sampler in 1830. Houses, trees, and dogs were popular motifs. The saying stitched at the top, transcribed below, was one of the most commonly used.

“When I am dead and in my grave

And all my bones are rotten.

When this you see remember me

Lest I should be forgotten”.

Needlework samplers are not only evidence of the importance of a practical skill, but are tangible links to the past and, specifically, to the individuals who made them. Each sampler contains unique identifying information about its maker: her name, age, geographic location, and even representations of important people and places in her life. The young girls who created these samplers have, with a needle, thread and a piece of fabric, permanently etched their lives into history.