By Lauren Ciriac Wenger

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, “patent medicines” in the form of elixirs, salves, and pills were at their height of popularity. These medicinal concoctions often claimed to ease an incredibly long list of ailments, and because of this they became known as “cure-alls.” Many of these claims were unfounded, though. While some did ease pain and other ailments, it was usually not because of the herbs or other touted ingredients, but rather alcohol, narcotics, or opiate substances. Patent medicines existed in a time before the addictive or dangerous effects of such drugs were known. These substances were called patent medicines not because the mixtures themselves were patented, but rather the designs of the labels and bottles. The ingredients were unregulated, and makers were not required to list the ingredients or their amounts on the label.

A few factors came together to contribute to the rise of patent medicines. Firstly, there was a lack of understanding of the progression and cure of illness. (It was not until the early to mid-1800s that Louis Pasteur conducted formal experiments on the relationship between germs and illness and published his results). Along with this, herbal home remedies had been handed down through generations, so this type of cure was familiar to many individuals. It was easy for entrepreneurs to take advantage of this trust. Plus, they took the labor out of making homemade medicines, and added supposed revolutionary ingredients.

The low prices of patent remedies catered to the masses that could not afford a physician. Illnesses, some quite serious, were fairly common during the 1800s, especially in children. Parents were desperate for ways to help their children. Finally, following the end of the Civil War, injured veterans sought pain medicines. Patent medicines were convenient palliatives.

The Hershey Story has a collection of several bottles and advertisements from this era. Excitingly, the bottles and documents in the collection represent some of the most commonly-used and renowned patent medicines of the turn of the century. These include names such as Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral, Old Dr. Townsend’s Sarsaparilla, and Paine’s Celery Compound.

The museum's collection contains a Maltine with Coca Wine bottle, in excellent condition. This product was advertised as a digestive aid and nutritional supplement, as the malted barley, wheat and oats were supposed to help build strong bones and body fat. However, erythroxylon coca, an extract of the cocaine plant, was also an ingredient in this tonic.

Old Dr. J. Townsend’s Sarsaparilla was marketed as “The Most Extraordinary Medicine in the World”, and claimed to purify the blood and, in turn, cure a list of other things including rheumatism, pimples, spinal issues, eye sores, ring worm, and dyspepsia. Symptoms of dyspepsia included poor digestion and malady of the stomach caused by a poor diet that included a lot of fat and starch. It was one of the most common diseases of the 19th century, and many patent medicines claimed they could ease its symptoms.

Other than sarsaparilla, ingredients in Old Dr. J. Townsend’s included various herbs, molasses, senna (a laxative) and 18 to 25 proof alcohol, depending on the variation. Alcohol was likely the most “effective” ingredient in several patent medicines, Townsend’s Sarsaparilla being one of these. Still, other brands of patent medicines contained additional substances that would be considered illegal today, especially for an over the counter medicine.

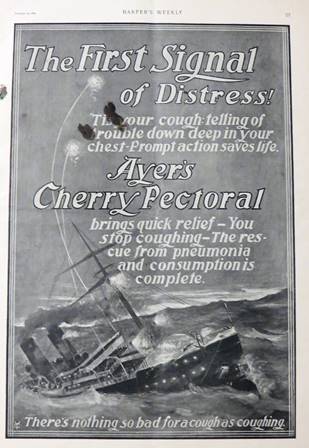

Physician James C. Ayer began to formulate and market remedies in the 1840s. The first of these was Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral, which became one of the most popular products of the patent medicine era. Though marketed as a remedy for everyone, it was also specifically advertised for children, and claimed to cure several dangerous afflictions such as whooping cough, tuberculosis, and influenza, as well as asthma and general colds and coughs. While the remedy did contain wild cherry extract, it also contained the opium-derivative morphine.

The main way companies advertised their remedies was through magazines and newspapers (which were becoming more widely distributed), as well as promotional materials like almanacs, calendars, and memo books. Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral was widely advertised, and by 1870 had contracts with 1,900 newspapers and periodicals. One of these was Harper’s Weekly.

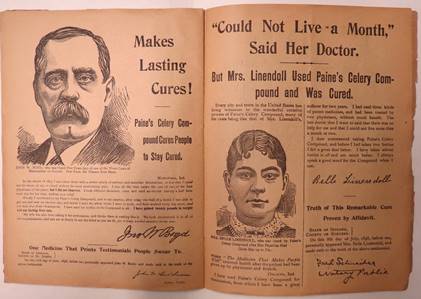

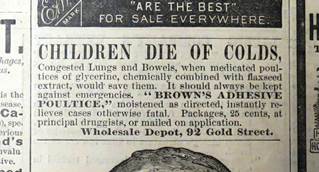

The Hershey Story also has several promotional almanacs given to consumers during the patent medicine era. Almanacs included not only weather forecasts, horoscopes, and calendars, but marketing for products in the form of testimonials and ads. Here is one published by Paine’s Celery Compound, a tonic for nerves, strength, and energy. Paine’s supposedly cured all sorts of diseases, and even brought people back from the brink of death. Patent medicine businesses were some of the first to market to consumers using psychological tactics—apparent in the ad for Brown’s Adhesive Poultice from an 1880s issue of Harper’s Weekly.

The media began to expose the dangers of patent medicines in the early 1900s. The Food and Drug Act of 1906 was a response to these unregulated medicines. While it did not ban alcohol, narcotics, or stimulants in medicines, these types of ingredients now had to be listed on the bottle. A complete listing of all ingredients was not required until 1938. More recently, laws have insisted that unregulated dietary supplements be labeled as “not evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration” and “this product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

While some patent medicines may have done more harm than good, we have this era to thank for several products that we still use to this day—although they do not include all of the same ingredients, and several are no longer used as medicines. Bromo-Seltzer, and the more well-known Alka-Seltzer, are still sold in drug stores. Vicks VapoRub, which used to be called “Vicks Magic Croup Salve”, is still a common household item. We still use Phillip’s Milk of Magnesia for our digestive ailments. Coca Cola, which used to contain extracts of the coca plant, and 7Up, which was originally called “Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda” and contained—you guessed it—lithium, became popular everyday beverages, free from dangerous substances. Many other sodas also came from this era, including Pepsi Cola, Dr. Pepper, Sarsaparilla Soda and Root Beer.

The story of patent medicines will always be an interesting one as we look back on the progression of society’s knowledge and understanding of health and illness. It is easy to see why people bought into these cures—they promised defense against many ailments, from those that were simply uncomfortable, like headaches, to the potentially deadly, like tuberculosis. Society is always progressing and we may find that one hundred years from now some of the medicines that we use on a daily basis are not ideal. The patent medicine artifacts at The Hershey Story serve as a reminder of our constant journey to understand and treat illness.