By Lauren Ciriac Wenger

In 1935, Milton Hershey purchased a collection that changed the size and scope of his museum, which had until that point featured only American Indian artifacts. The new collection primarily contained household and decorative arts items representative of Pennsylvania German daily life during the 1700s and 1800s. The collection had belonged to general store owner George H. Danner, of Manheim, Pennsylvania, and was for sale by the executors of Danner’s estate.

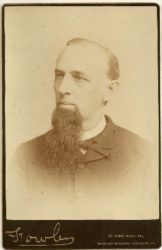

George Danner assembled the collection between 1870 and 1917, and displayed it on the third floor of his store, which he reserved solely for his collection. He even made the room fireproof, and installed an elevator to haul large collectibles upstairs. He enjoyed giving tours to guests and explaining detailed histories of notable objects.

Danner cited his mother’s china cupboard filled with dishware as a main source of inspiration for his interest in collecting antiques. So it is no surprise that his collection contained over 2,000 ceramics of varying styles, including Lusterware, Creamware, and Gaudy Dutch; and he obtained many of these pieces in an interesting way. He would load his wagon with fashionable new Queensware from his store, and travel around offering to exchange people’s “outdated” antiques for the new dishes. Most did not realize the value of their older dishes and gladly traded with Danner.

Creamware gets its name from its yellowish-white glaze. It was developed in the mid 18th century by Staffordshire, England potters trying to find a product to compete with the imported Chinese porcelain market. Creamware proved ideal for everyday use, as it was lightweight and had a clean, polished look. It was also affordable for the average household.

Transfer printing onto ceramics began in the late 1700s as a way to mass-produce decorative styles. The design was engraved into a copper plate, which was inked and stamped onto a piece of tissue paper, and then carefully transferred to the ware. Scenes depicted are often pastoral, historic, or patriotic. Also common were important buildings familiar to the users of the wares, as seen in this plate from The Hershey Story’s collection that shows the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. The various scenes encouraged collecting (for example, some people might collect government buildings and others historic scenes) and the plates grew in popularity during the late 1800s.

Though created in England, the colors and designs of Gaudy Dutch ceramics of 1810-1830 were designed to appeal to Pennsylvania Germans. Reds, blues, greens, pinks, and yellows appeared bright and bold against a light background, and designs included birds, flowers, and fruit—common themes in PA German-crafted items. Basic utilitarian tablewares were available, such as plates, tea cups and saucers, creamers, and sugar bowls.

Lusterware is a type of porcelain with an iridescent metallic glaze that was created between 1820 and 1860. It was made in various metallic colors. This copper color was created by adding a gold wash. Lusterware heightened in popularity as gaslights became more common in homes, especially with wealthier individuals. The lamps highlighted the shine of the wares. There was even a trend in using grouped lusterware as decorative centerpieces for dinner parties.

One can see why George Danner enjoyed collecting such items. They are beautiful, intricate examples of art and craftsmanship, and the history behind their manufacture and use is truly fascinating. No doubt Danner would have enjoyed explaining the details of these pieces to the many people that paid a visit to his collection.